Lotus & Pyramid

Lotus & Pyramid

The Sign

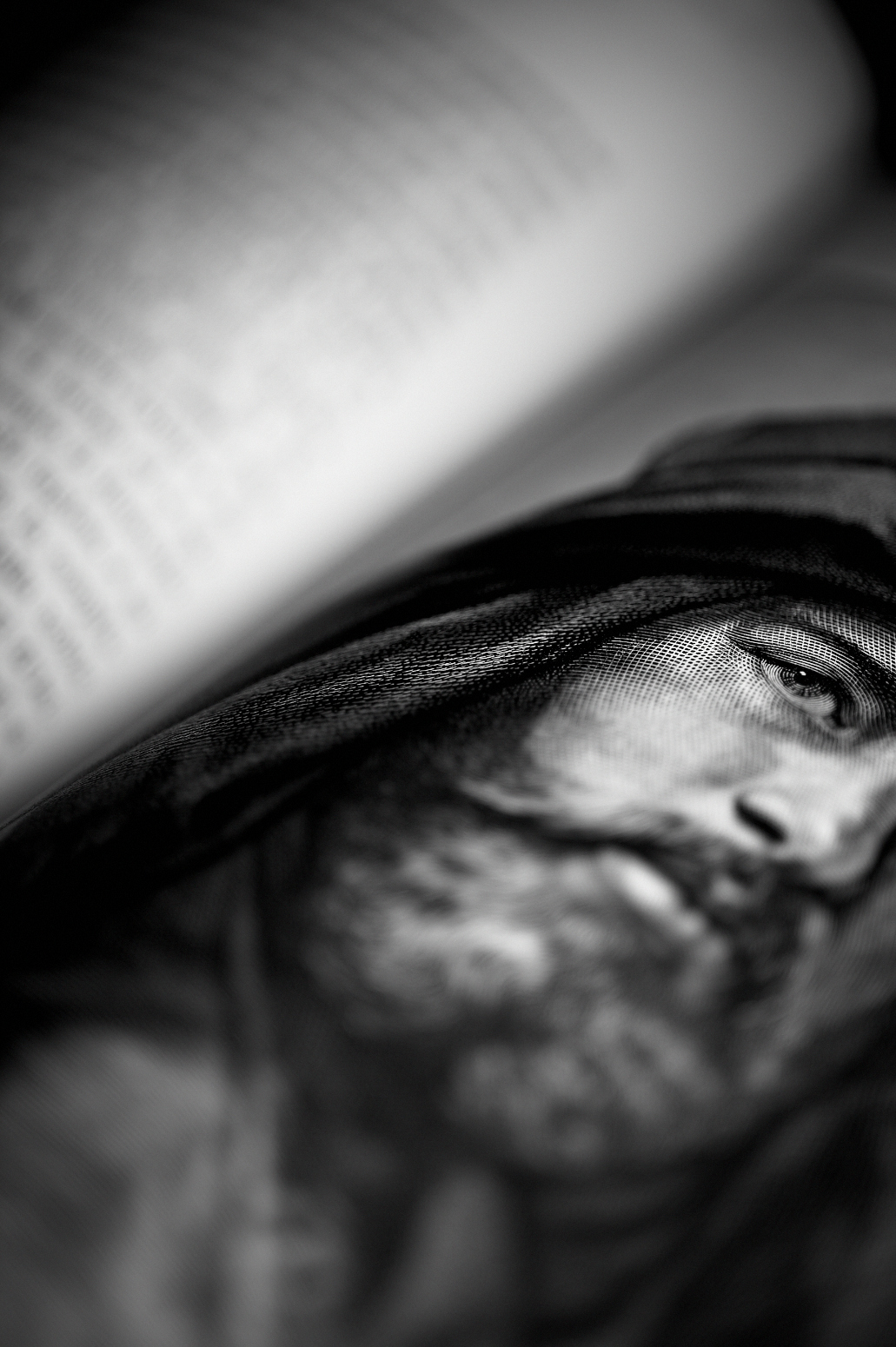

In the past, travel books were accompanied by images long before the invention of photography. These works—illustrated with a more fantastic than accurate view—enriched the imagination of readers who dreamed of Egypt as a mysterious land full of ancient monuments and populated by strange creatures. In the coming years, towards the mid-nineteenth century, the pictorial imagination of the East was replaced by the more scientific perspective of designers, architects, and scribes whose masterpieces appear in many works, such as the beautiful publications in the Description d’Égypte of the Napoleonic expedition or the works of Lepsius and Rosellini. In the service of study, art made a significant contribution to the newly born science of Egyptology. However, some artists continued to capture the exotic nature of Egypt, passing it on to their audience. David Roberts was one of the most influential artists of that period, spending two and a half months in Egypt in 1838, drawing and painting the most significant monuments and scenes of local life. The Belgian Louis Hague, an expert lithographer, prepared Roberts’ works for publication over the next eight years. His colourful and often romanticised works, accompanied by texts by famous writers of the time, such as Binon, Birch, and Brockedon, have always been prevalent among collectors. Other renowned artists visited Egypt, bringing back beautiful images: William Henry Bartlett, David Wilkie, Frederick Catherwood, Edward Lear, Owen Jones, and with Orientalism—through representatives such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, Eugène Delacroix, and Étienne Dinet—the French transformed the representation of Egypt into a distinct painting movement.

The Invention

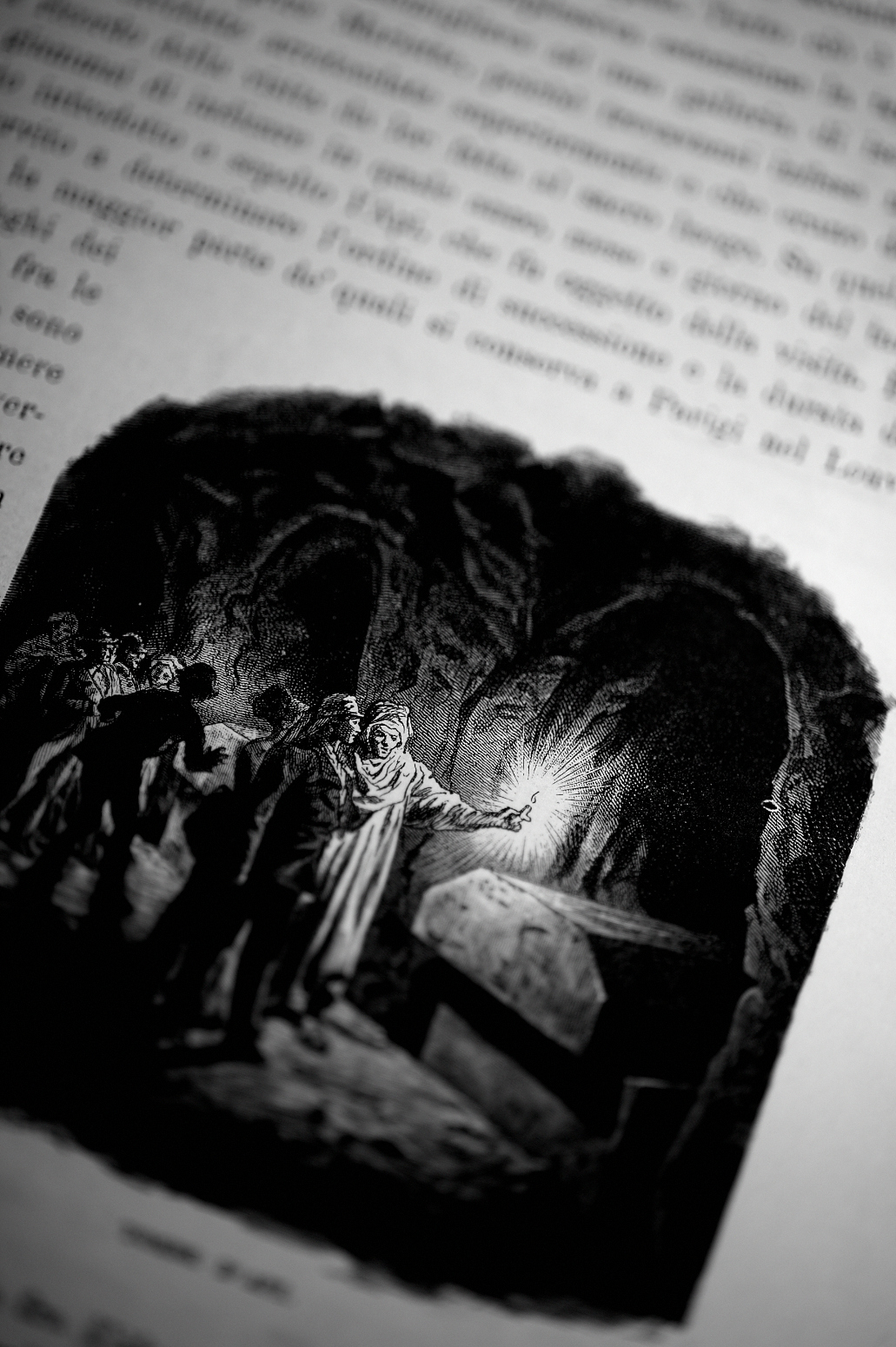

In 1839, one of the earliest forms of photographic processes was invented, gaining great resonance in France as elsewhere in Europe: the daguerreotype. This method allowed for the depiction of images objectively without relying on the artist’s creative work. Unfortunately, this technique created a single image that could not be duplicated, which is why the shots of the first photographers—to be depicted in books—were reproduced in the form of engravings. Between 1841 and 1843, the French optician Noël Paymal Lerebours published Excursions Daguerriennes: Vues et Monuments les Plus Remarquables du Globe, an album in two volumes illustrated with aquatints made using daguerreotypes. The images were taken in various parts of the world by individuals remembered as the first photographers in history: Frederic Goupil-Fesquet, his uncle Horace Vernet, Hector Horeau, and Joly de Lotebinière. In travel books, drawings—often made by the travellers themselves—began to be replaced by engravings derived from images obtained through the camera obscura. Any loss of romantic mood—with the undoubted gain in accuracy and objectivity—was compensated by the engraver, who often added people to animate the view since the long exposure times did not allow for capturing movement.

The Journey

Pictures in books were accompanied by engravings taken from photographs to replace drawings. My interest in travel literature began with the discovery of some prints by David Roberts. His romantic vision of Egypt fascinated me so much that it led me to investigate this captivating subject. Collecting travel books was my choice to learn the stories of many travellers, some of whom spent a few months in Egypt while others stayed there for the rest of their lives. Among these adventurers were consuls, wealthy aristocrats, and scholars—various people, including the dishonest and the generous, the snobbish and the simple. I encountered the generosity and soul of Belzoni, the curiosity and respect of Burckhardt, the intelligence of Drovetti, and the dangerous devotion of Finati.

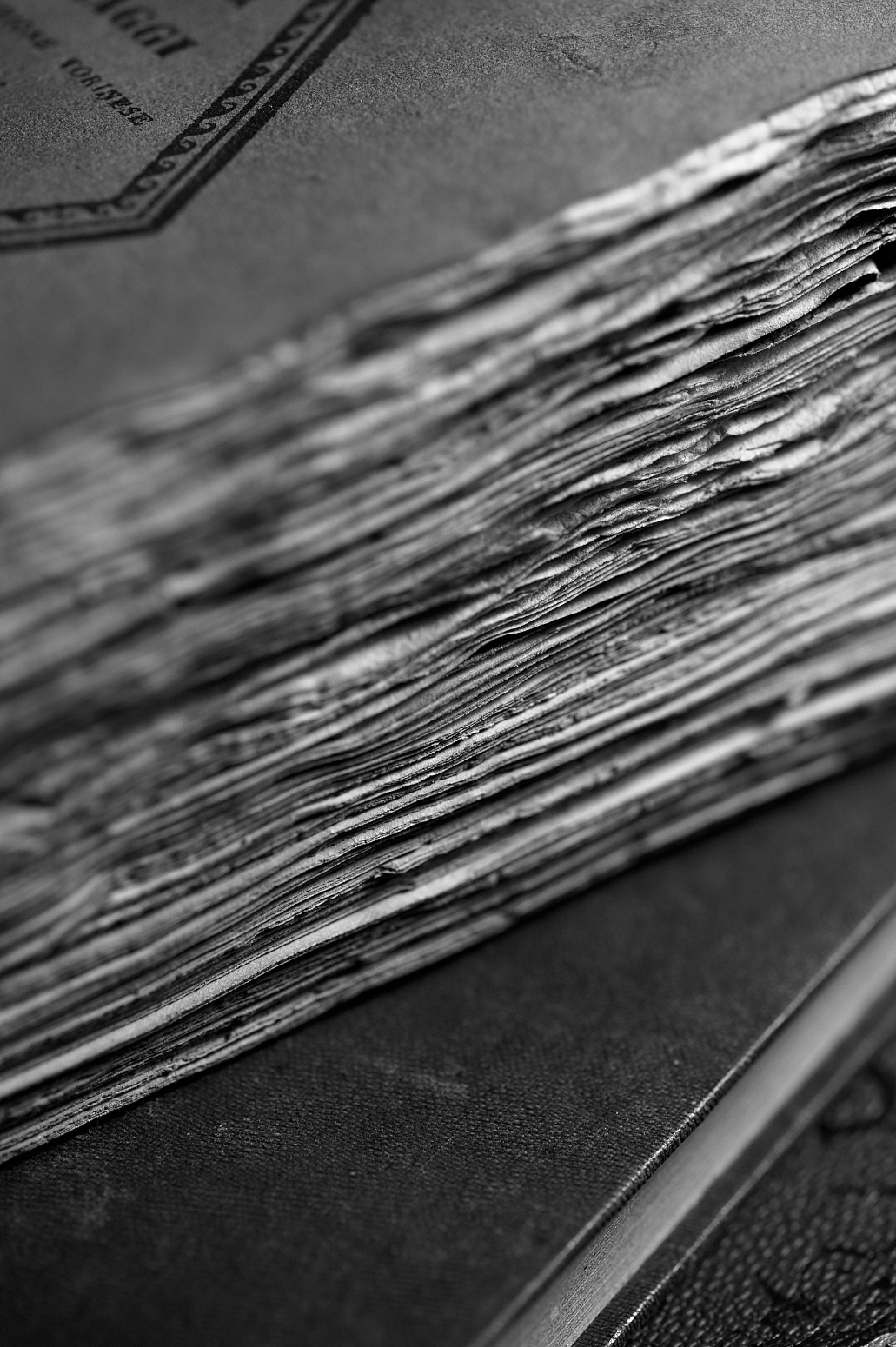

Although the reading experience took me beyond the images accompanying the text—some books were completely short of images—these illustrations helped me dream about the words that filled the pages. My love of books fostered a passion for the men and women who knew how to live and chose to recount their experiences. I envied their adventures and cherished the written word; the illustrations helped me imagine those words, creating a world of pages where I dreamed of a country in another era. It isn’t easy to do justice to the readings that have accompanied me for years and continue to move me. With these images—perhaps also a palimpsest, as Lucie Duff-Gordon wrote—I hope to trace a long path of memory without losing the sense of travel. I replaced colours with the dark shades of many shadows caressing the travellers’ notebooks, illuminated by the lamps inside their tents. Colour represents life, reality, and journey. Black and white allowed me to evoke and unify sometimes different figures. The images were only a frame for writing, but isn’t the picture itself a narration for images? It makes sense to collect these photographs as beloved evidence of personal discovery, aiming to spark the curiosity of others to unveil the memory of a bygone era travelled by people who knew how to give meaning to their journeys and lives. I want to conclude my impressions with a text from a traveller, the Italian Carlo Vidua, who, in a letter from 1810, described what travelling meant to him. Reading these words, I think it is clear what his motivation was—like many others—to dedicate his life.

Carlo Vidua's Letter

“You know that there are so many ways of travelling, as a savant, as a man of the world, as a lover of literature, as a grand gentleman, as a ladies’ man, as a meticulous researcher of every notable thing, as an artist, as a draftsman, as a messenger, as a financier or merchant, etc., etc. As I am not and do not want to be anything in this world, and as I have told you many times, I would not want to take the trouble of being mediocre in something, I have adopted a system of travelling completely different from all of these people, at least so it seems to me. My principal objective is to see the important things of whatever kind and, above all, to get to know the way of thinking of various classes of people. When I go to a country, I try to get to know two classes of people: the nobility and some men of letters. The nobility allows me to see the world and its customs and to understand other ways of thinking because, generally speaking, a man of such rank who has wits, many relationships, and is in touch with many, understands their ways of thinking. To the contrary, a shopkeeper, for example, knows well only his shop and that which is beneath him and so forth. The men of letters could help me see, profitably, that which is most beautiful and to benefit from their reason, when they have it, which does not happen so often.”

This project was featured in the American magazone LensWork.